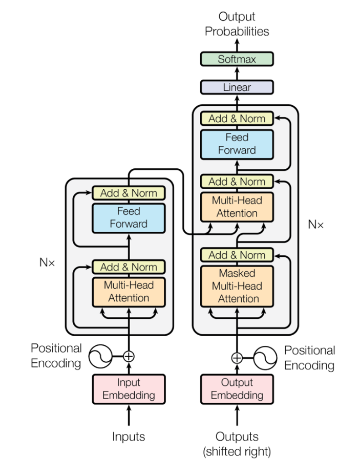

The Original Transformer

- Position Embeddings: sines and cosines

$$

PE_{\text{(pos, 2i)}} = \sin(\text{pos}/10000^{2i/d_\text{model}})

$$

$$

PE_{\text{(pos, 2i+1)}} = \cos(\text{pos}/10000^{2i/d_\text{model}})

$$

- Feed Forward Activation: ReLU

$$

FFN(x) = \max(0, xW_1+b_1)W_2 + b_2

$$

- Norm: LayerNorm, applied after the residual stream is added back (Post-Norm)

Normalization

Pre-vs-post Norm

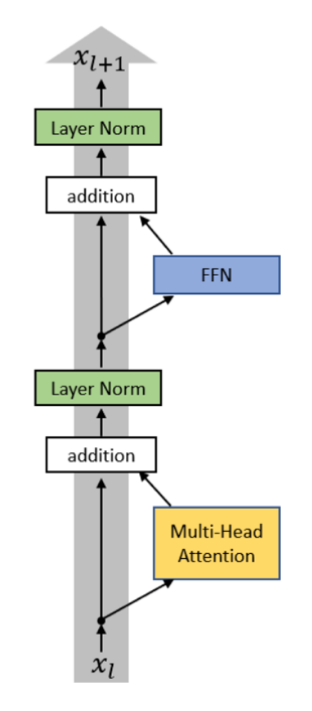

- Originally, LayerNorm was applied after the “sublayer output + residual connection”:

-

- Here, input $x_l$ is first sent to the attention module. Then, output of the attention is summed with the residual stream.

- Then, the normalized summation is sent to the feedforward layer, which is again summed with the residual stream.

- Finally, a LayerNorm is applied again before it is sent to the next layer.

$$

\begin{align}

x_{l, i}^{post, 1} &= MultiHeadAttn(x_{l, i}^{post}, [x_{l, 1}^{post}, \dots, x_{l, n}^{post}]) & \text{Sublayer Output (Attention)}\\

x_{l, i}^{post, 2} &= x_{l, i}^{post} + x_{l, i}^{post, 1} & \text{Residual Connection}\\

x_{l, i}^{post, 3} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{post, 2}) & \text{Norm after sublayer output + residual connection, i.e. PostNorm} \\

x_{l, i}^{post, 4} &= ReLU(x_{l, i}^{post, 3} W^{1,l}+b^{1, l})W^{2, l} + b^{2, l} & \text{Sublayer Output (Feedforward)}\\

x_{l, i}^{post, 5} &= x_{l, i}^{post, 3} + x_{l, i}^{post, 4} & \text{Residual Connection}\\

x_{l, i}^{post, 6} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{post, 5}) & \text{PostNorm} \\

\end{align}

$$

-

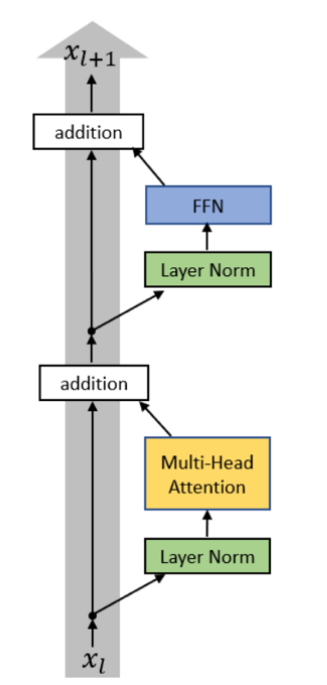

- Now, almost all modern LMs use pre-norm, which simply changes the order of the sandwich:

$$

\begin{align}

x_{l, i}^{pre, 1} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{pre}) & \text{Norm before sublayer output + residual connection, i.e. PreNorm} \\

x_{l, i}^{pre, 2} &= MultiHeadAttn(x_{l, i}^{pre, 1}, [x_{l, 1}^{pre, 1}, \dots, x_{l, n}^{pre, 1}]) & \text{Sublayer Output (Attention)}\\

x_{l, i}^{pre, 3} &= x_{l, i}^{pre} + x_{l, i}^{pre, 2} & \text{Residual Connection}\\

x_{l, i}^{pre, 4} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{pre, 3}) & \text{PreNorm} \\

x_{l, i}^{pre, 5} &= ReLU(x_{l, i}^{pre, 4} W^{1,l}+b^{1, l})W^{2, l} + b^{2, l} & \text{Sublayer Output (Feedforward)}\\

x_{l, i}^{pre, 6} &= x_{l, i}^{pre, 3} + x_{l, i}^{pre, 5} & \text{Residual Connection}\\

\end{align}

$$

In this case, LayerNorm is also applied before it is sent to the output head:

$$

x_{Final, i}^{pre} = LayerNorm(x_{L+1, i}^{pre})

$$

-

- Reason for the switch:

- Training stability

- Removes the need for the warmup iterations

- Lets you use larger learning rates

- Reason for the switch:

- Other approaches:

- Grok and Gemma-2 does double norm:

$$

\begin{align}

x_{l, i}^{double, 1} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{double})\\

x_{l, i}^{double, 2} &= MultiHeadAttn(x_{l, i}^{double, 1}, [x_{l, 1}^{double, 1}, \dots, x_{l, n}^{double, 1}])\\

x_{l, i}^{double, 3} &= LayerNorm(x_{l_i}^{double, 2})\\

x_{l, i}^{double, 4} &= x_{l, i}^{double} + x_{l, i}^{double, 3}\\

x_{l, i}^{double, 5} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{double, 4}) \\

x_{l, i}^{double, 6} &= ReLU(x_{l, i}^{double, 5} W^{1,l}+b^{1, l})W^{2, l} + b^{2, l}\\

x_{l, i}^{double, 7} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{double, 6})\\

x_{l, i}^{double, 8} &= x_{l, i}^{double, 4} + x_{l, i}^{double, 7}\\

\end{align}

$$

-

- Olmo 2 does only non-residual post norm:

$$

\begin{align}

x_{l, i}^{olmo, 1} &= MultiHeadAttn(x_{l, i}^{olmo}, [x_{l, 1}^{olmo}, \dots, x_{l, n}^{olmo}])\\

x_{l, i}^{olmo, 2} &= LayerNorm(x_{l_i}^{olmo, 1})\\

x_{l, i}^{olmo, 3} &= x_{l, i}^{olmo} + x_{l, i}^{olmo, 2}\\

x_{l, i}^{olmo, 4} &= ReLU(x_{l, i}^{olmo, 3} W^{1,l}+b^{1, l})W^{2, l} + b^{2, l}\\

x_{l, i}^{olmo, 5} &= LayerNorm(x_{l, i}^{olmo, 4}) \\

x_{l, i}^{olmo, 6} &= x_{l, i}^{olmo, 3} + x_{l, i}^{olmo, 5} \\

\end{align}

$$

LayerNorm vs. RMSNorm

- Original transformer (along with GPT 3/2/1, OPT, GPT-J, BLOOM) uses LayerNorm:

$$

y = \frac{x – \mathbb{E}[x]}{\sqrt{Var[x] + \epsilon}} * \gamma + \beta

$$

- Most new models (e.g. LLaMA-family, PaLM, Chinchilla, T5) use RMSNorm:

$$

y = \frac{x}{\sqrt{\dfrac{||x||^2_2}{n} + \epsilon}} * \gamma

$$

-

- Removes bias term $\to$ Fewer parameters to store

- Does not calculate and subtract the mean $\to$ Fewer operations

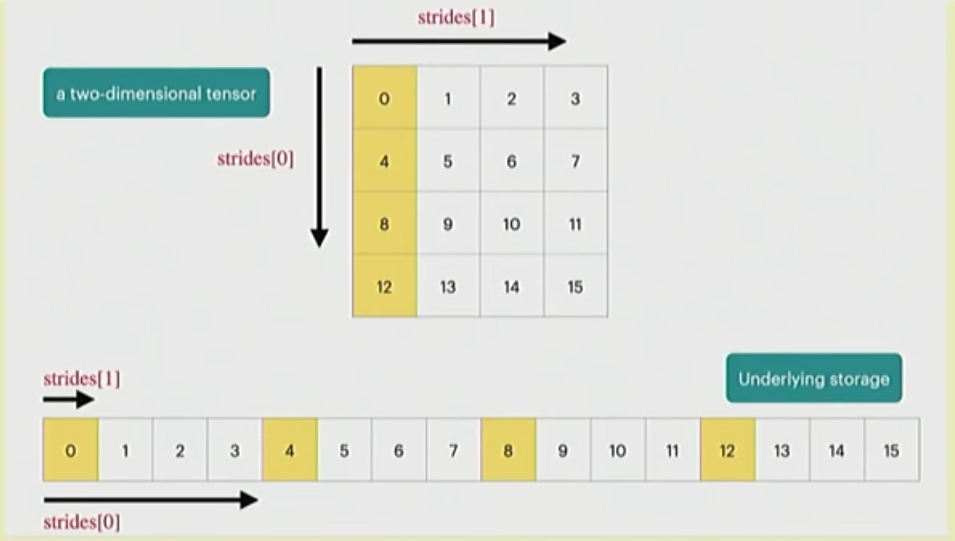

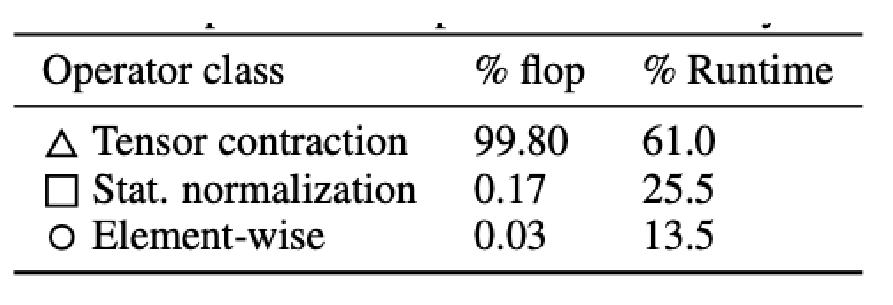

- Even though most of the FLOPs happen during the matrix multiplication, bias term and normalization operation can still increase the runtime due to required data movement operations:

Bias Terms

- Original transformer and earlier models used bias terms:

$$

FFN(x) = \max(0, xW_1 + b_1)W_2 + b_2

$$

- Most newer (but non-gated) implementations get rid of the bias term for performance gain and to store less parameters:

$$

FFN(x) = \sigma(xW_1)W_2

$$

Activations

- Earlier, ReLU and GeLU were the most commonly used.

- ReLU:

$$

FF(x) = \max(0, xW_1)W_2

$$

- GeLU:

$$

\begin{align}

FF(x) &= GELU(xW_1)W_2 &\\

GELU(x) &:= x \Phi(x) & \Phi(.) \text{ is the Gaussian CDF}

\end{align}

$$

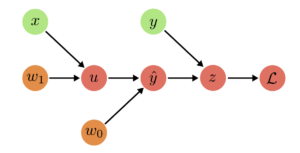

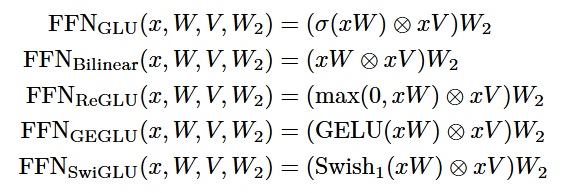

- New trend is to use gated activations. Idea is:

- Project the input into two different vectors, let’s say $g$ and $p$.

- $g$ is sent through a nonlinear function, turns into “gate weights”.

- $g$ and $p$ is then element-wise multiplied.

- So, instead of two weight matrices per FFN like in the original transformer, now we have 3.

- That is why gated models use smaller internal dimensions by about 2/3, so the number of parameters for FFN is roughly the same.

- Examples:

Serial and Parallel Layers

- Standard transformer block applies first attention, and then the feedforward layer.

- Serial implementation is still the standard practice, but there are alternative approaches for speed gain.

$$

\begin{align}

y &= x + \underbrace{MLP(\text{LayerNorm}(x + \text{Attention}(\text{LayerNorm}(x))))}_{\text{Working on the normalized residual stream + attention layer outputs}} & \text{Serial Transformer Block} \\

y &= x + \underbrace{MLP(\text{LayerNorm}(x))}_{\text{Working only on normalized input}} + \text{Attention}(\text{LayerNorm}(x)) & \text{Parallel Transformer Block}

\end{align}

$$

Position Embeddings

- Sine – Cosine Embeddings

- Use sine and cosine to keep track of the token positions.

- Embedding for a token $x$ at position $pos$:

$$

\begin{align}

Embed(x, pos) &= v_x + PE_\text{pos}\\

PE_{(pos, 2i)} &= \sin(pos/10000^{2i/d_\text{model}}) \\

PE_{(pos, 2i+1)} &= \cos(pos/10000^{2i/d_\text{model}}) \\

\end{align}

$$

-

- Idea is to create an embedding matrix $PE$, where each row corresponds to a position vector. In the beginning dimensions of the vector, you have higher frequency functions, and in the ending dimensions you have lower frequency functions.

- So, dimensions near the end are better to understand the ballpark position, and the earlier dimensions are to precisely determine the position.

- Assume $d_\text{model} = 1024$

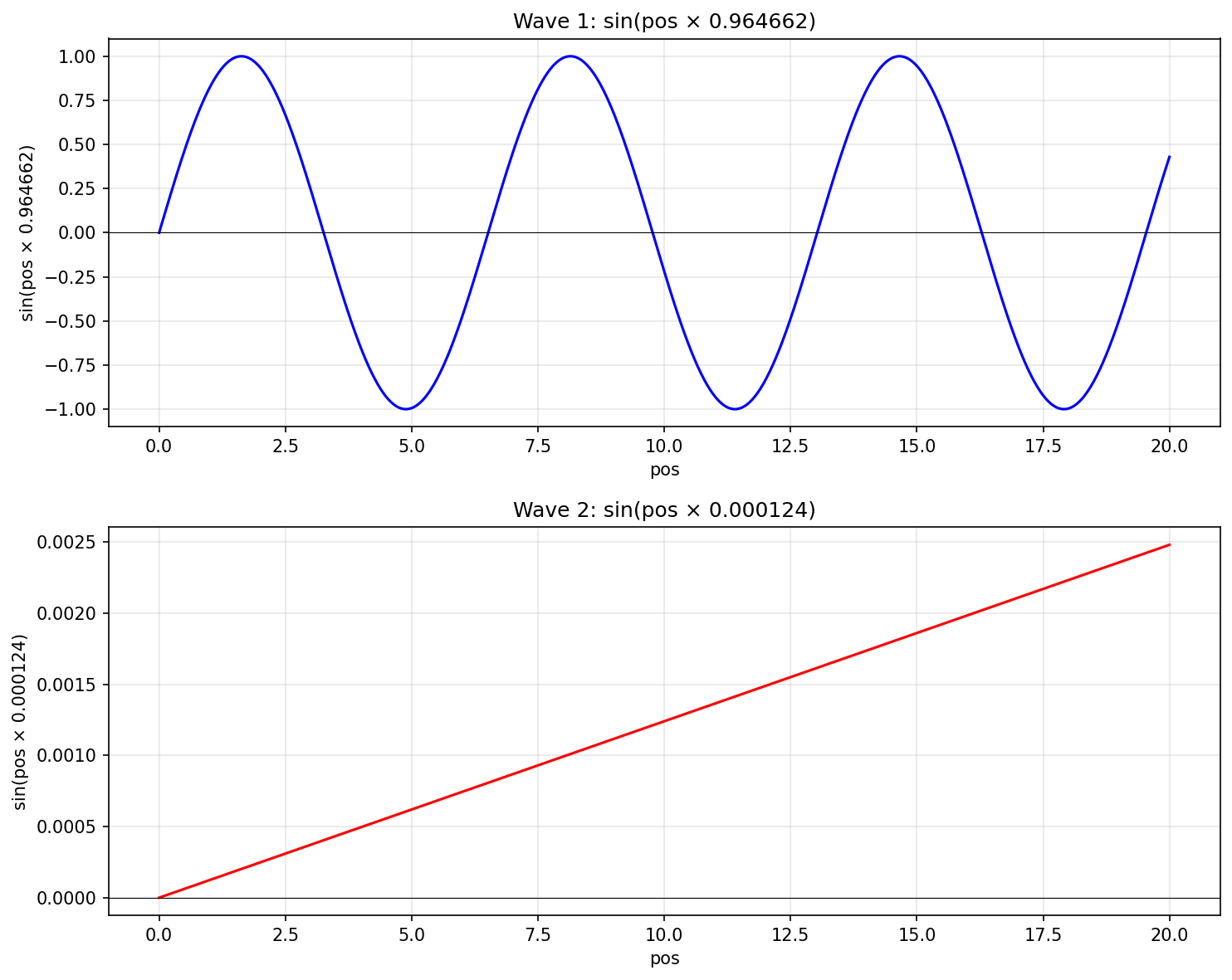

- This means we have $512$ sine waves, and $512$ cosine waves, each with different frequency. Let’s focus on the sine waves at $i=2$, and $i=500$.

$$

\begin{align}

\sin(pos \times \frac{1}{10000^{4/1024}}) &\approx \sin(pos\times 0.964662) & (i=2)\\

\sin(pos \times \frac{1}{10000^{1000/1024}}) &\approx \sin(pos\times 0.000124) & (i=500)

\end{align}

$$

-

-

- Now, notice that the sine wave with $i=500$ changes much slower compared to the wave with $i=2$, because it has lower angular frequency, i.e $0.000124 < 0.964662$. That is why, that dimension changes much slower ($\sim 7800$ times slower).

- Here, you can see how they change for the first $20$ positions:

-

-

-

- First function will complete its cycle around $6.51$ positions and start repeating, while the second function completes its cycle in around $50645$ positions:

-

$$

\begin{align}

\omega_{i=2} = \frac{2\pi}{T} = 0.964662 \implies T \approx \frac{2\times3.14}{0.964662} \approx 6.51\\

\omega_{i=500} = \frac{2\pi}{T} = 0.000124 \implies T \approx \frac{2\times3.14}{0.000124} \approx 50645

\end{align}

$$

-

-

- So, the high frequency function can only determine position up to $6.51$ units, and then has to start repeating.

- Lower frequency function completes its cycle much later, so it can determine positions up to $50645$ units. But because it changes so slowly, it can not discriminate between e.g. $pos=2$ and $pos=3$ (See how close they are in the plot above).

- That was the rationale behind using trigonometric functions.

- And also they thought model could learn to exploit the trigonometric identities to do “relative positioning too”, but this doesn’t seem to be the case.

-

But idea was:

$$

\begin{align}

& \sin(pos+k) = \sin(pos)\cos(k) + \cos(pos)\sin(k)\\

& \cos(pos+k) = \cos(pos)\cos(k) – \sin(pos)\sin(k)\\ \\

\implies &

\begin{bmatrix}

\sin(pos+k)\\

\cos(pos+k)

\end{bmatrix} =

\underbrace{ \begin{bmatrix}

\cos(k) & \sin(k) \\

-\sin(k) & \cos(k)

\end{bmatrix}}_{A}\times

\underbrace{\begin{bmatrix}

\sin(pos)\\

\cos(pos)

\end{bmatrix}}_{\text{PE}}

\end{align}

$$

-

-

- And this is just a linear operation, a matrix multiplication between some weights $A$ and the positional embeddings matrix PE.

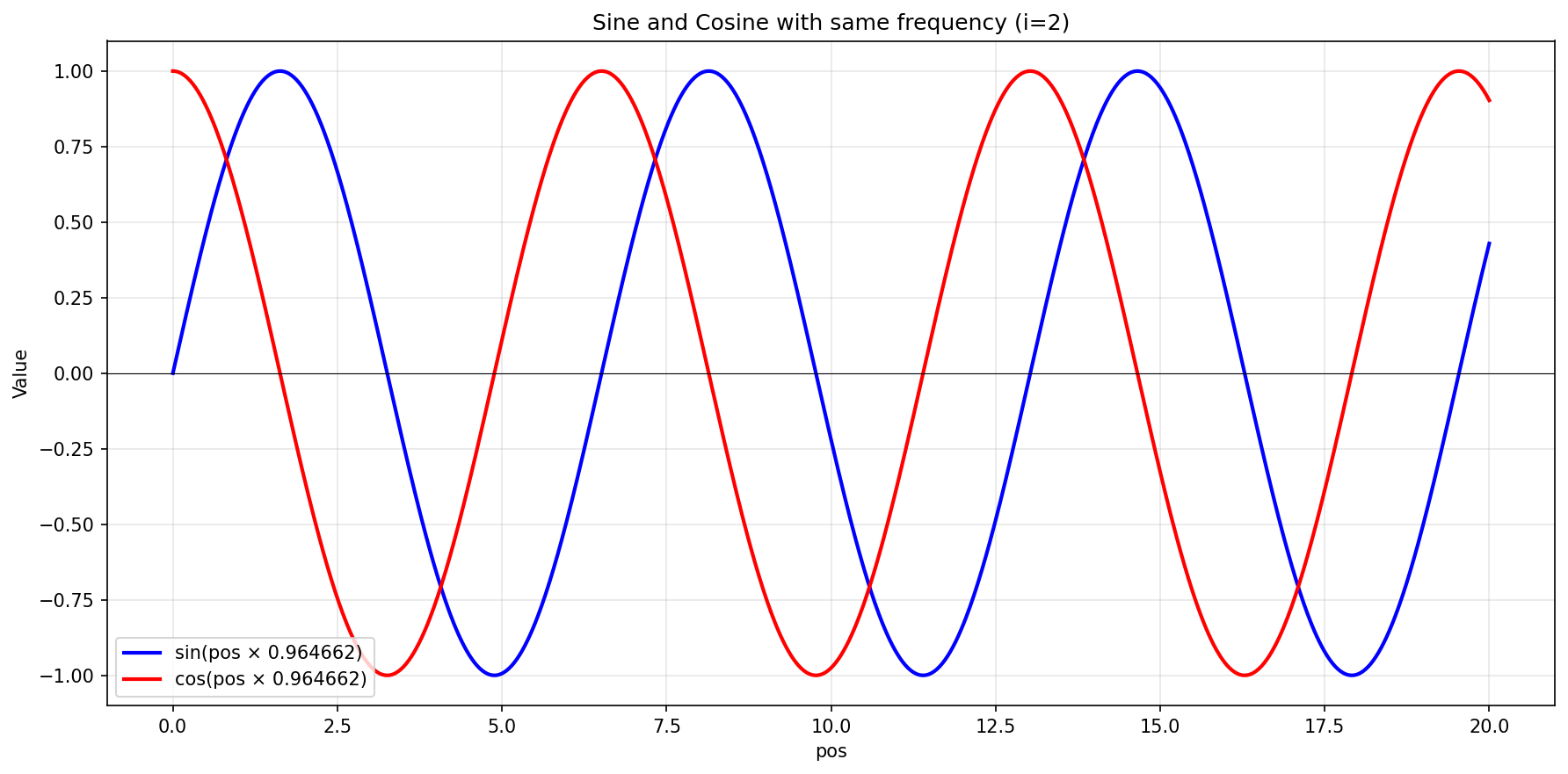

- Furthermore, instead of using only sine, they also used cosine at the same frequency. This helps to differentiate between e.g. position 3 and 6, where for $i=2$, sines will have almost exactly the same value but cosines will be different:

-

- Absolute Embeddings

- Used in GPT-1, 2, 3 and OPT

- Instead of using fixed positional embeddings like the trigonometric ones before, turn it into a trainable layer

$$

Embed(x, pos) = v_x + u_\text{pos}

$$

- Relative Embeddings

- Used in T5, Gopher, Chinchilla

- Instead of adding a learned or fixed position embedding to the token, use a learned embedding based on the offset between the “key” and “query” in the attention layers.

- A fixed number of embeddings are learned, corresponding to a range of possible key-query offsets.

- Start with the classic scaled dot-product attention between $x_i$ and $x_j$:

$$

e_{ij} = \frac{\overbrace{(x_iW^Q)}^{Query}\overbrace{(x_jW^K)^T}^{Key}}{\underbrace{\sqrt{d_z}}_{Normalization}}

$$

- Define two learnable vectors for the relationship between $x_i$ and $x_j$, one on the value level and one on the key level: $a_{ij}^V, a_{ij}^K \in \mathbb{R}^{d_a}$.

- These relationship vectors can be shared between different attention layers.

- Then, you can simply add these relative vectors to where you originally use key and value vectors.

- To calculate the context vectors:

$$

\underbrace{z_i}_{\text{Context vector for token at position i}} = \sum_{j=1}^n \alpha_{ij}\underbrace{(\underbrace{x_jW^V}_{\text{Value Vector for $x_j$}} + \underbrace{a_{ij}^V}_{\text{Value vector for positions [i] and [j]}})}_{\text{Modified value vector}}

$$

- To calculate the attention scores:

$$

e_{ij} = \frac{\overbrace{x_i W^Q}^{\text{Query vector for $x_i$}}\overbrace{(\overbrace{x_jW^K}^{\text{Key vector for $x_j$}} + \overbrace{a_{ij}^K}^{\text{Key vector for positions [i] and [j]}})^T}^{\text{Modified key vector for $x_j$}}}{\sqrt{d_z}}

$$

- Because it is impractical to model all possible differences, and arguably not needed, maximum distance $|i – j|$ is clipped at some value $k$ and then gets repeated. This means it will be possible to model $2k+1$ unique distances. ($k$ in both directions):

$$

\begin{align}

a_{ij}^K &= w_\text{clip(j-i, k)}^K \\

a_{ij}^V &= w_\text{clip(j-i, k)}^V \\

\text{clip}(x, k) &= \max(-k, \min(k, x))

\end{align}

$$

-

- Efficient implementation:

- While theoretically it is nicer to think in terms of “modifying” the key and value vectors, efficient implementation actually does not modify the key matrices but adds another matrix multiplication, which is mathematically equivalent:

- Efficient implementation:

$$

e_{ij} = \frac{x_iW^Q(x_jW^K)^T+x_iW^Q(a_{ij}^K)^T}{\sqrt{d_z}}

$$

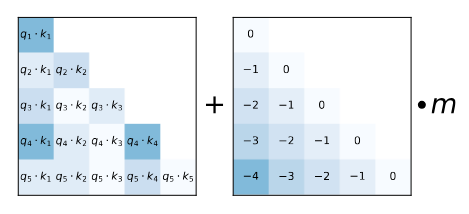

- ALiBi (Attention with Linear Biases)

- Similar to the idea of relative embeddings, can be considered a special case.

- We are modifying the attention score calculation, using non-learnable bias terms:

$$

\begin{align}

e_{ij} = \frac{x_iW^Q(x_jW^K)^T}{\sqrt{d_z}} + m\cdot(j-i)

\end{align}

$$

- Here, $m$ is a predetermined scalar changing the slope for the different heads, going up to $\frac{1}{2^8}$. For 8 attention heads, they have $\frac{1}{2^1}, \frac{1}{2^2}, \dots, \frac{1}{2^8}$ and for 16 attention heads, it is $\frac{1}{2^{0.5}}, \frac{1}{2^{1}}, \dots, \frac{1}{2^{7.5}}, \frac{1}{2^{8}}$. (So, basically start from $2^{\frac{-8}{n}}$ and go up to $2^{-8}$) .

- Idea is, for each token, causal attention calculation is done only based on the per-token representation so far, and then bias term provides the position information by punishing the distant terms, i.e. a closer token will have $-m + \text{score}$ and if the distance in between is 10 tokens, it will be $-10m + \text{score}$. And each head “punishes” the distance separately, based on their pre-determined slope:

- As the distance gets longer, the $m\times\text{distance}$ term will start to dominate the actual score, so applying softmax to them will create outputs near $0$, i.e. because you are pushing the far-away tokens to be more negative/smaller, and closer tokens only slightly, softmax will favor the closer tokens.

- Expectation is, that this is going to learn to generalize to unseen context lengths, thanks to its recency bias. However, this could be problematic when you need long-term dependencies.

- RoPE (Rotary Positional Embeddings)

- Think of the modeling of the relative distance in the attention layers:

$$

\begin{align}

\langle f_q(x_m, m), f_k(x_n, n) \rangle &= g(x_m, x_n, m-n)

\end{align}

$$

where $x_m$ is the query token at position $m$, and $x_n$ is the key token at position $n$. The goal is to end-up with a function $g$, that should calculate an attention score based on three inputs:

-

- $x_m$: Embedding for $x_m$

- $x_n$: Embedding for $x_n$

- $m-n$: Distance between the positions of $x_m$ and $x_n$

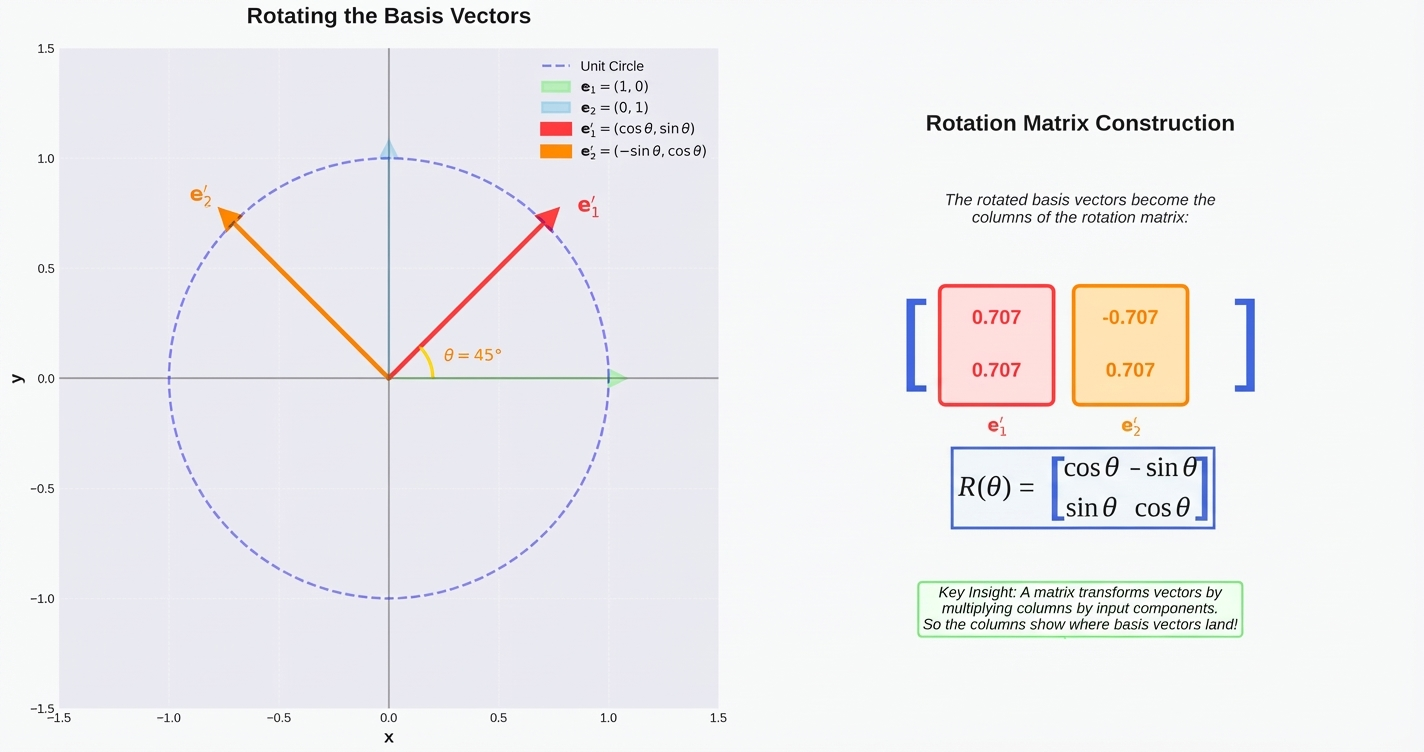

- First, remember the rotation matrices in 2D, and how they are defined using $\sin$ and $\cos$ functions of the same frequency:

- Original transformer used pairs of sines and cosines as well, but for absolute encoding. Now, idea is to use the same sines and cosines, but instead of adding them to the token embeddings, we will rotate the key and query vectors at attention layers. Rotation matrix is defined similarly:

$$

\begin{align}

R_{\Theta, m}^d &= \begin{pmatrix} \cos m\theta_1 & -\sin m \theta_1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \sin m\theta_1 & \cos m \theta_1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \cos m\theta_2 & -\sin m \theta_2 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \sin m\theta_2 & \cos m \theta_2 & \cdots & 0 & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \cos m \theta_{d/2} & -\sin m\theta_{d/2} \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & \sin m \theta_{d/2} & \cos m \theta_{d/2} \\ \end{pmatrix}\\[1em] \\

&= \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{R}(\theta_1) & \mathbf{0} & \cdots & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{R}(\theta_2) & \cdots & \mathbf{0} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{0} & \cdots & \mathbf{R}(\theta_{d/2}) \end{pmatrix} \end{align} \\

$$

- So, we have $d/2$ different rotation matrices, which are defined based on cosine and sine functions with different frequencies. Base frequency is the same one as they had in the original transformer:

$$

\Theta = \{ \theta_i = \frac{1}{10000^{2(i-1)/d}}, i \in [1, 2, \dots, d/2] \}

$$

- Then, you have to rotate your query and key vectors, and every two dimension rotate in different frequencies (frequencies have been changed so their movement can be shown in the animation):

- Then, you simply rotate both your query and key vectors when you are calculating the attention scores:

$$

\begin{align}

q’_m &= R^d_{\Theta,m} W_q x_m & \text{(Rotated query vector for token at position m)}\\

k’_n &= R^d_{\Theta, n} W_k x_n & \text{(Rotated key vector for token at position n)}\\

e_{ij} &= \dfrac{(R^d_{\Theta,m} W_q x_m)^T (R^d_{\Theta, n} W_k x_n)}{\sqrt{d}} = \dfrac{x^T_m W_q \overbrace{R_{\Theta, (n-m)}^d}^{\text{Relative rotation}} W_k x_n}{\sqrt{d}}

\end{align}

$$

- So, rotating the query vector and value vector by their absolute positions corresponds to using a rotation matrix based on relative positions, as:

$$

\begin{align}

R(n\theta) \cdot R(-m\theta) &=

\begin{bmatrix}

\cos n\theta & -\sin n\theta \\ \sin n\theta & \cos n\theta \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \cos(-m\theta) & -\sin(-m\theta) \\ \sin(-m\theta) & \cos(-m\theta) \end{bmatrix}\\[1em] &= \begin{bmatrix} \cos n\theta & -\sin n\theta \\ \sin n\theta & \cos n\theta \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \cos m\theta & \sin m\theta \\ -\sin m\theta & \cos m\theta \end{bmatrix}\\[1em] &= \begin{bmatrix} \cos n\theta \cos m\theta + \sin n\theta \sin m\theta & \cos n\theta \sin m\theta – \sin n\theta \cos m\theta \\ \sin n\theta \cos m\theta – \cos n\theta \sin m\theta & \sin n\theta \sin m\theta + \cos n\theta \cos m\theta \end{bmatrix}\\[1em] &= \begin{bmatrix} \cos(n-m)\theta & -\sin(n-m)\theta \\ \sin(n-m)\theta & \cos(n-m)\theta \end{bmatrix}\\[1em] &= R((n-m)\theta)

\end{align}

$$

- Efficient Implementation

- Because the rotation matrix is sparse, it is possible to do the multiplication computationally more efficient with:

$$

R^d_{\Theta,m} \mathbf{x} =

\begin{pmatrix}

x_1 \\

x_2 \\

x_3 \\

x_4 \\

\vdots \\

x_{d-1} \\

x_d

\end{pmatrix}

\otimes

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos m\theta_1 \\

\cos m\theta_1 \\

\cos m\theta_2 \\

\cos m\theta_2 \\

\vdots \\

\cos m\theta_{d/2} \\

\cos m\theta_{d/2}

\end{pmatrix}

+

\begin{pmatrix}

-x_2 \\

x_1 \\

-x_4 \\

x_3 \\

\vdots \\

-x_d \\

x_{d-1}

\end{pmatrix}

\otimes

\begin{pmatrix}

\sin m\theta_1 \\

\sin m\theta_1 \\

\sin m\theta_2 \\

\sin m\theta_2 \\

\vdots \\

\sin m\theta_{d/2} \\

\sin m\theta_{d/2}

\end{pmatrix}

$$

Hyperparameters

Field seems to converge on some hyperparameters:

- Feedforward – model dimension ratio

- Usually is scaled up to 4 times of the model dimension and scaled back down.

$$

d_{ff} = 4 d_\text{model}

$$

-

- GLU variants: Because researchers wanted to keep the parameter count similar, they tend to scale down the hidden size of the feedforward layer:

$$

d_{ff} \approx \frac{8}{3}d_\text{model}

$$

- Number of heads and head dimension

- Usually, number of heads and dimension of the heads is chosen in a way, such that their multiplication is equal to the model dimension:

$$

d_\text{model} = n_\text{heads} \times d_\text{head}

$$

- Depth (number of layers) vs. width (model dimension) debate

- Earlier, there were very deep models (BLOOM, T5 v1.1) with $d_\text{model}/n_\text{layer} > 170$, and very wide models (T5, GPT-2) with $d_\text{model}/n_\text{layer} < 50$, but newer models usually have the following aspect ratio:

$$

100 < \dfrac{d_\text{model}}{n_\text{layer}} < 160 $$

-

- The choice of depth and width is also affected by your networking constraints and the type of parallelisms you can do. e.g. Tensor parallel that lets you train wider networks need fast network, while pipeline parallel where you can shard the model per layer can get away with a slower network.

- But empirical research (OpenAI Scaling paper) shows the sweet spot is around 70 – 150

- Vocabulary sizes

- Monolingual models usually have around 30,000 – 50,000 token vocabulary size

- Multilingual and newer models have between 64,000 – 255,000 token vocabulary size

- Training regularization

- Initially, a lot of models were using dropout

- Nowadays, it seems like most don’t use dropout anymore, but switched to using weight decay

- However, weight decay is not used for regularization, as it looks like it has no effect on overfitting (i.e. ratio of training loss to validation loss), but rather has an interesting relationship to dynamic learning rates like cosine LR decay, and ends up facilitating faster training and higher accuracy. Furthermore, weight decay stabilizes training with

bfloat16. - More on this at

D'Angelo, Francesco, et al. "Why do we need weight decay in modern deep learning?." <em>Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems</em> 37 (2024): 23191-23223.

Stability Tricks

- Softmaxes -> The problem child

- Used in the final layer and also attention layers

- Solution for the Final Layer: Z-loss (from 2014 – Devlin et. al., for decoding speed, later used for stability in 2022 by PaLM)

- Z-loss refers to the normalization factor in softmax. Softmax if defined as:

$$

P(x)_i = \sigma(x)_i = \frac{\exp(x_i)}{\underbrace{\sum_{j=1}^d \exp(x_j)}_{\text{Z($x$), i.e. Softmax Normalizer}}}

$$

-

-

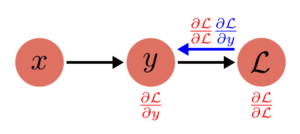

- It turns out, by encouraging the normalizer to be close to $1$, we can get more stable training runs. As you can write the log likelihood as log softmax, loss calculation on softmax can be written as:

-

$$

\begin{align}

L(x) &= \log\left(\frac{\exp(x_i)}{Z(x)}\right) \\

&= \log(\exp(x_i)) – \log(Z(x))

\end{align}

$$

, assuming logit $i$ represents the correct logit.

-

-

- Then, to encourage the $Z(x)$ to be $1$, you can simply push the $\log(Z(x))$ towards 0, with a coefficient of $\alpha$ where $\alpha$ determines the amount of “encouragement”:

-

$$

\begin{align}

L(x) &= \left[ \log(P(x)_i) – \alpha (\log(Z(x)) – 0)^2 \right] \\

&= [\log(P(x)_i) – \alpha \log^2 (Z(x)) ] \\

&= [\underbrace{\log(\exp(x_i)) – \log(Z(x))}_{\text{Standard Softmax Loss}} – \underbrace{\alpha\log^2(Z(x))}_{\text{Z-loss}}]

\end{align}

$$

-

-

- In PaLM, $\alpha = 10^{-4}$.

- So, the idea is to add additional MSE loss on $\log(Z(x))$. In theory, you can apply this to all softmax layers but in practice, everyone just applies it to the last layer.

- For the attention softmaxes, another trick is used, namely QK Norm.

- Idea is simple. Before you calculate the attention with dot product of $q$ and $k$, apply LayerNorm / RMSNorm on them.

-

Attention Heads

Cost of the Multi-Head Attention

There are various alternatives to multi-head attention, devised in order to make best use of the GPU time. To understand why, let’s calculate the cost of attention in each head.

Every head computes three projections first:

- $XW^Q \to$ Projects inputs to the query vectors

- $XW^K \to$ Projects inputs to the key vectors

- $XW^V \to$ Projects inputs to the value vectors

(We will drop the batch size from calculations for simplicity)

Assuming $X \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times d}$ and $W^Q, W^K, W^V \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d_a}$:

- Computational cost of projections: $O(ndd_a)$.

- Memory cost: $O(nd + dd_a)$

- You could also include the output activations for memory, i.e. $O(nd + dd_a + nd_a)$ but since $d > d_a$ almost always, I drop it)

Then, the resulting matrices $Q, K \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times d_a}$ are multiplied to get $QK^T$:

- Computational cost: $O(n^2d_a)$

- Memory cost: $O(nd_a + n^2)$

Now, the resulting matrix $QK^T \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n}$ will have softmax applied to it.

- Computational cost: $O(n^2)$

- Memory cost: $O(n^2)$

Now that we have the attention scores, we want to create the context vectors by multiplying the attention scores and the value vectors. As we are multiplying two matrices with sizes $(n\times n) \times (n \times d_a)$:

- Computational cost: $O(n^2d_a)$

- Memory cost: $O(n^2 + nd_a)$

Now, this is the key insight here. As we are doing this for every head, all of the calculations get multiplied with $h$ (except the memory cost of the input matrix, it doesn’t get read from the memory for each head)! So, so far we have

- Computational cost: $O(hndd_a + hn^2d_a + hn^2 + hn^2d_a) \to O(hndd_a + hn^2d_a)$

- Note: This can further simplify depending on the relationship between $n$ and $d$, but with the modern models we are not sure what the sequence length is going to be compared to the dimension of the model

- Memory cost:

$$

\begin{align}

O(&\underbrace{nd}_{\text{Input to attention for projections}} + \underbrace{hdd_a}_{\text{Output of the projections}} + \underbrace{hnd_a}_{\text{Input for attention score}} + \underbrace{hn^2}_{\text{Output for attention score}} + \\

& \underbrace{hn^2}_{\text{Softmax Activations}} + \underbrace{hn^2}_{\text{Input to context vector calculation}} + \underbrace{hnd_a}_{\text{Output of the context vector calculation}}) \\

& \to O(\underbrace{nd}_{\text{Input to attention for projections}} + \underbrace{hn^2}_{\text{Attention score outputs + softmax activations + context vector calculation input}})

\end{align}

$$

Then, after head outputs are combined (this is a memory operation, so you can maybe incur an $O(nd)$ memory cost again but doesn’t change the calculations), you have the final projection $CP$, with $C \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times d}, P \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times d}$ context matrix and projection matrix, respectively. This final operation has:

- Computational cost: $O(nd^2)$

- Memory cost: $O(nd + d^2)$

Combining everything together,

- Total computational cost: $O(hndd_a + hn^2d_a + nd^2)$

- Total memory cost: $O(nd + hn^2 + d^2)$

Now, we can do some assumptions based on the general conventions. Usually, $d = h\times d_a$. Then:

- Computational cost: $O(nd^2 + n^2d)$

- Memory cost: $O(nd + hn^2 + d^2)$

So, this computational cost and memory cost showed us something. With the current conventions, number of heads has negligible effect on the computational cost but memory cost is highly dependent on the number of heads. Ideally, we want to improve arithmetic intensity, that is the ratio of computational cost to memory cost. As we do not want to have smaller hidden dimensions or shorter sequences, we tend to play around with the number of heads to improve the arithmetic intensity.

Batching Multi-Head Attention

- For simplicity, we dropped the batch from the calculations. Lets add it back:

- Computational Cost: $O(bnd^2 + bn^2d)$

- Memory Cost: $O(bnd + bhn^2 + d^2)$ (Projection matrix is independent of the batch size, so it does not get multiplied by $b$)

- Arithmetic Intensity: $O\left(\frac{bnd^2 + bn^2d}{bnd + bhn^2 + d^2}\right)$

- During training, this can be accepted, because by batching you can parallelize all the operations and still utilize the GPUs fully.

- However, during the inference time, each attention calculation has to wait for the memory movement. So, you get into Generate -> IO Wait -> Generate -> IO Wait -> Generate … workflow. This under-utilizes the GPU (if not enough parallel requests) and causes slow responses (due to waiting for memory movement).

Multi-Query Attention (MQA)

- Proposed Solution: Have queries per head, but share the $W^K$ and $W^V$

- What does it achieve:

- In MHA, for each head data movement per key and value matrices is $O(hnd_a) = O(nd)$.

- By having only one Key and Value matrix, we decrease the memory movements by a factor of $h$ -> $O(nd_a)$

- Even though this does not change the full complexity analysis, it provides significant speed-ups in reality because you significantly reduce the data movement from KV cache (this is primarily an inference optimization).

Grouped-Query Attention (GQA)

- Proposed Solution: MQA can decrease performance, so have shared key and value matrices, e.g. first key and value matrices will be used by the first 3 heads, the second will be used by the heads 3-6 and so on.

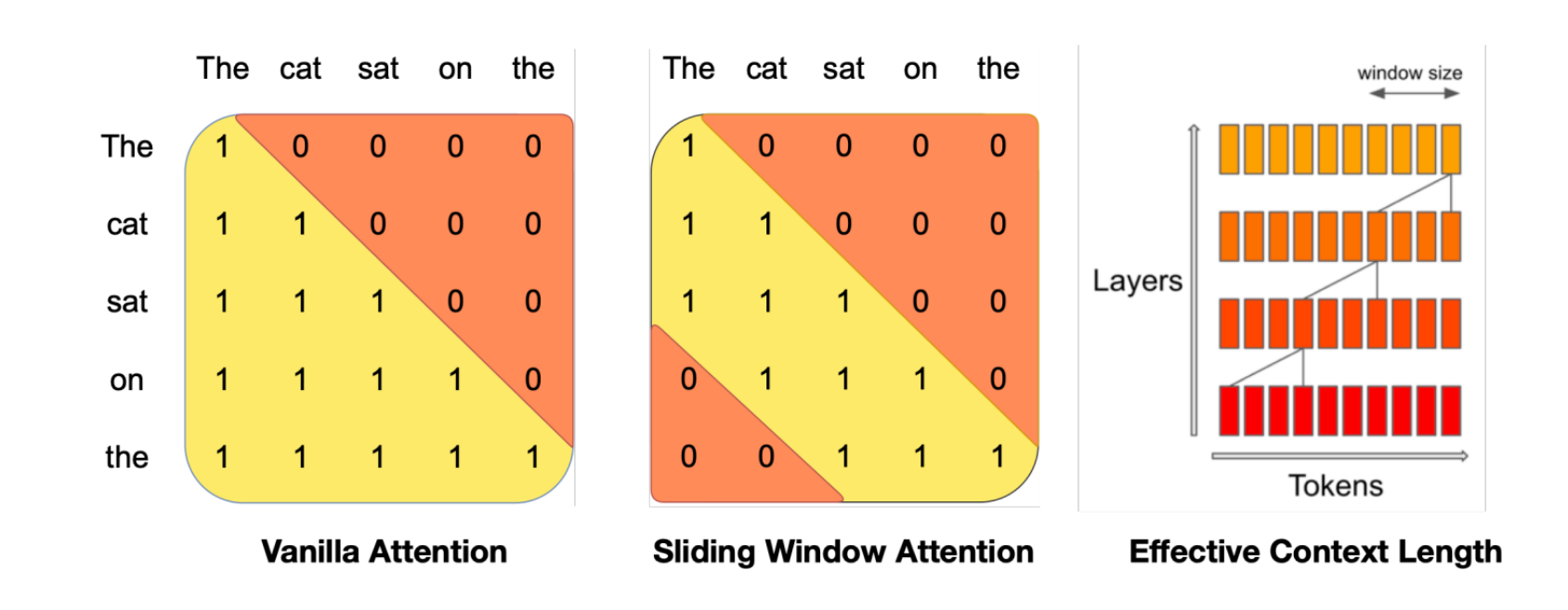

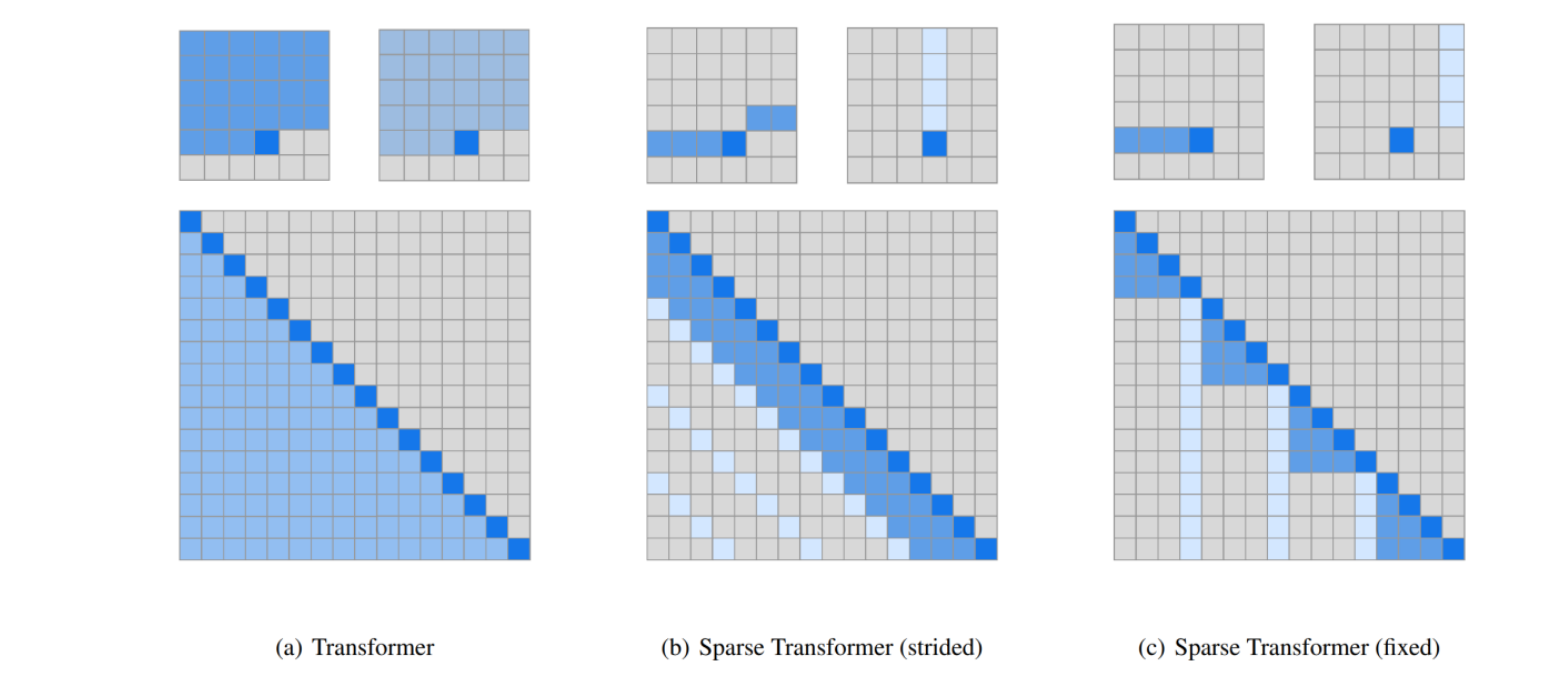

Sparse and Sliding Window Attentions

- Basically, consider only the closest tokens:

- Sliding Window attention:

- Sparse Transformers:

Combining Long- and Short-Range Information

- E.g. in Cohere Command A, every 4th layer is a full attention layer with no positional embeddings (NoPE).

- Other attention layers are Sliding Window + Grouped Query Attention with RoPE.

Resources:

Language Modeling from Scratch Lecture Notes – Percy Liang, Tatsunori Hashimoto, Stanford University https://stanford-cs336.github.io/spring2025/

Shazeer, Noam. “Glu variants improve transformer.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.05202 (2020).

Vaswani, Ashish, et al. “Attention is all you need.” Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

Shaw, Peter, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Ashish Vaswani. “Self-Attention with Relative Position Representations.” Proceedings of NAACL-HLT. 2018.

Xiong, Ruibin, et al. “On layer normalization in the transformer architecture.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020.

Ivanov, Andrei, et al. “Data movement is all you need: A case study on optimizing transformers.” Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 3 (2021): 711-732.

Press, Ofir, Noah A. Smith, and Mike Lewis. “Train short, test long: Attention with linear biases enables input length extrapolation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.12409 (2021).

Su, Jianlin, et al. “Roformer: Enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding.” Neurocomputing 568 (2024): 127063.

Devlin, Jacob, et al. “Fast and robust neural network joint models for statistical machine translation.” proceedings of the 52nd annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). 2014.

Chowdhery, Aakanksha, et al. “Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 24.240 (2023): 1-113.

Andriushchenko, Maksym, et al. “Why do we need weight decay in modern deep learning?.” (2023).

“Multi-Query Attention is All You Need.” Fireworks AI, https://web.archive.org/web/20251224025619/https://fireworks.ai/blog/multi-query-attention-is-all-you-need

Ainslie, Joshua, et al. “Gqa: Training generalized multi-query transformer models from multi-head checkpoints.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.13245 (2023).

Child, Rewon. “Generating long sequences with sparse transformers.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.10509 (2019).

Jiang, Albert Q., et al. “Mistral 7B.” arXiv, 10 Oct. 2023, doi:10.48550/arXiv.2310.06825.

Other figures are mostly created with the help of Claude Sonnet 4.5.